Peripheral-nerve rerouting is an exciting surgical

procedure that has considerable potential for restoring significant

function after spinal cord injury (SCI). Basically, with this procedure,

peripheral nerves (i.e., those outside of the spinal cord and brain)

emanating from the cord above the injury site are surgically rerouted

and connected to those below the injury site. This reestablishes a functional neuronal connection from

the brain to previously dormant muscle or sensory systems.

injury site. This reestablishes a functional neuronal connection from

the brain to previously dormant muscle or sensory systems.

A key force behind developing this procedure into a

real-world SCI therapy has been Dr. Shaocheng Zhang, of Changhai Hospital, Shanghai, China. Because he has treated

over a 100 people with SCI, he has made routine a seemingly challenging

neurosurgical procedure. In addition to Zhang’s work, Dr. Giorgio

Brunelli, University of Brescia, Italy has greatly contributed to

developing the procedure.

After I met Zhang at a World

Health Organization (WHO) SCI conference, he invited me to Shanghai

last December to become the first American to observe firsthand his

peripheral-nerve-rerouting surgery. Because his hospital, Shanghai’s

largest, is military affiliated, this invitation to a Paralyzed Veterans

of America (PVA) representative clearly was a bridge-building, goodwill

gesture. It would certainly be a promising sign for the future if

military-affiliated organizations from two countries that have had

historically some animosity could work together to find solutions for a

problem that bows to no flag or political system

East Meets West:

An impressively modern city with 16-million

residents, Shanghai is located near the juncture of the Yangtze River

and the East China Sea. As China enters the World Trade Organization,

Shanghai seems destined to reclaim its historical role as the

country’s most international city.

Its downtown skyline - with the world’s third tallest

skyscraper and an even-taller, space-needle-like tower - rivals that of

virtually any city.

Although few residents spoke English, its presence

was everywhere. For example, many road, building, and billboard signs

were in English; police cars were prominently labeled with the word

“police”; airplane and train schedules were announced in English;

Christmas carols were piped-in at the ubiquitous, familiar fast-food

restaurants; and rock, rap, and jazz music was played on the radio.

Considerable hospitality and friendship were

extended to me, including much sympathy for the World Trade Center

terrorist attack. Overall, there seemed to be a sincere desire to move

into the twenty-first century as friends of America, not adversaries,

and to work together for mutually beneficial economic growth.

Procedure:

Unlike

spinal cord nerves, peripheral nerves have considerable regenerative

potential and the ability to establish new neuronal connections.

Building upon these capabilities, Zhang surgically reroutes and

connects a peripheral nerve that emanates from the spinal cord above the

point of injury to nerves or nerve roots below the injury. Hence, a

viable neuronal connection from the brain to the previously

paralysis-affected body area is created, restoring some function.

Unlike

spinal cord nerves, peripheral nerves have considerable regenerative

potential and the ability to establish new neuronal connections.

Building upon these capabilities, Zhang surgically reroutes and

connects a peripheral nerve that emanates from the spinal cord above the

point of injury to nerves or nerve roots below the injury. Hence, a

viable neuronal connection from the brain to the previously

paralysis-affected body area is created, restoring some function.

The nature of the restored function depends upon

the specific functions that the target nerves serve (e.g., leg muscle

function, bladder and bowel control, sensation, etc). For example, the

rerouted nerve could be connected to a nerve that controls urination, or

it could be reconnected to nerve that controls upper leg muscles.

Alternatively, if the rerouted nerve is connected

to a general nerve root system, function in the overall physical area

controlled by this system will be restored. One surgical rerouting

designed to restore a specific function does not preclude a future

rerouting to restore a different function. (Because this article

extensively refers to different spinal cord and dermatome sensation

levels, readers are encouraged to consult the illustrations for

reference).

Many possible rerouting arrangements exist. Zhang

commonly reroutes one of the intercostal nerv es

that lead from the spinal cord around each rib to the sternum. If the

intercostal nerve is not long enough to reach the target nerve site

below the injury level, a segment of the sural nerve (isolated from the

calf) is attached to the intercostal nerve.

es

that lead from the spinal cord around each rib to the sternum. If the

intercostal nerve is not long enough to reach the target nerve site

below the injury level, a segment of the sural nerve (isolated from the

calf) is attached to the intercostal nerve.

If the injury site is above the thoracic area where

the intercostal nerves originate, other peripheral nerves can be

selected. For example, in several cases, Zhang has rerouted the ulnar

nerve, which leads down to the wrist originating from the C8-T1 spinal

cord region, a procedure Italy’s Brunelli has also used.

In addition to the intercostal and ulnar nerves,

peripheral-nerve-rerouting options can restore function for virtually

any level of injury. For example, in high-level injuries, functional

peripheral nerves above the injury site (e.g .,

cervical plexus nerve branches originating from the higher cervical

regions) can be connected to nearby dysfunctional nerves below the

injury site (e.g., brachial plexus nerves originating from the lower

cervical regions), potentially restoring respiratory ability to a

previously ventilator-dependent quadriplegic.

.,

cervical plexus nerve branches originating from the higher cervical

regions) can be connected to nearby dysfunctional nerves below the

injury site (e.g., brachial plexus nerves originating from the lower

cervical regions), potentially restoring respiratory ability to a

previously ventilator-dependent quadriplegic.

Zhang’s patients have lost little function in the

original area served by the donor nerve because of nerve redundancy, the

availability of multiple nerve branches, or the creation of alternative

connections. For example, rerouting one of the many rib-associated,

intercostal nerves will result in little functional loss. In the case of

ulnar nerve rerouting, alternative nerve connections can be created to

the hand and wrist.

Although improvement in some cases is quickly

apparent, restored function will gradually accrue over 12-18 months

depending upon the specific surgical complexity.

While the procedure isn’t precluded for older

patients, younger patients with greater inherent regenerative potential

often benefit more from peripheral nerve rerouting.

In addition, as more time passes after injury, the surgery may

become less feasible, especially for lower-level injuries.

In spite of intimidating neuroanatomical

terminology, peripheral-nerve rerouting is conceptually relatively easy

to understand. For example, visualize a house in which the power to the

back bedroom is lost (i.e., area below the injury) due to a burned-out

master electrical cable (i.e. the spinal cord injury). Instead of fixing

the master cable, you disconnect the wire that powers the living-room

television (i.e., a nerve to the rib or wrist region), tunnel it through

the walls, and splice it directly to the bedroom wiring, circumventing

the damaged section of master cable.

If the redirected wire isn’t long enough to reach

the bedroom, you splice an intervening piece of wire (i.e., the sural

nerve) cut out from a part of the basement you rarely use. In order not

to lose television function, you simply insert the TV plug into another

living room outlet (i.e., establish alternate connections). Although

this procedure may not be as desirable as replacing the master cable,

you, nevertheless, now have power in the back bedroom.

Case Studies:

I observed Zhang carry out peripheral

nerve-rerouting operations in three individuals with SCI. In addition, I

have interacted with two former patients.

Case #1:

Last year, 31-year old Yang acquired a T9-10 injury after falling

at work. The surgery’s

primary goal was to restore some of Yang’s lower extremity function,

especially bladder control. Yang’s 3-4-hour surgery was the most

involved of the three operations I observed.

Initially, Zhang detached for later use a sural

nerve segment from Yang’s calf. He

then proceeded to isolate an intercostal nerve from Yang’s rib region,

maintaining the nerve’s connection to the spinal cord. Next, Zhang

exposed Yang’s sacral nerve roots that control urogenital muscles.

After he sutured the detached sural nerve segment to the intercostal

nerve to make it long enough to reach this sacral region, the combined

intercostal-sural nerve was connected to the sacral nerve roots.

Yang demonstrated some restored sensation in body areas

controlled by the recipient sacral nerves (see dermatome chart) hours

after surgery (This quick initial recovery is due to decompression).

Case 2:

Although 31-year old Wang had retained some hip function after

his lumbar injury, he had lost bladder control. In this case, a nerve

that led to Wang’s functional hip was connected to a nearby

dysfunctional nerve that served the urinary system. Specifically, the

gluteus inferior nerve (originating from the L-5, S-1,2 spinal-cord

level) that innervates the gluteus maximus muscle was connected to the

injury-affected pudendal nerve (originating from the S-2,3,4 spinal-cord

level) that serves the urogenital muscles. Because of the nerves’

physical proximity, no intervening graft was needed. Overall, this was a

much less complicated operation, requiring only an hour to complete.

Case 3: Although

involving a peripheral nerve SCI treatment, the third surgery

represented a fundamentally different procedure, which Zhang has

performed in more than 12 patients, and is included because of its

radical nature.

This case involved

36-year old Chu, who had recently become a C-4 quadriplegic due to a

construction accident. In Chu’s operation, detached, sural nerve

segments were inserted directly into his injured spinal cord. These

segments were initially scraped to expose nerve fibers and, after scar

tissue was removed from and incisions made in the remaining cord,

inserted lengthwise without suturing. The next day, Chu, who had

previously possessed only residual bicep function, was able to move his

hands.

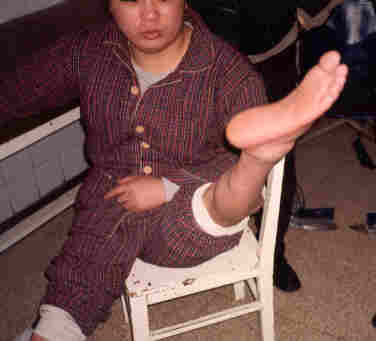

Follow-Up Case 1: Huocheng

acquired a T11-12 injury in a 1997 motorcycle accident when he was 25.

The following year, Zhang rerouted an intercostal nerve from one side of

Huocheng’s body to the lumbar nerve roots and, in turn, an intercostal

nerve from the opposite side of his body to the sacral nerve roots.

These two nerve reroutings together restored much of

Case 1: Huocheng

acquired a T11-12 injury in a 1997 motorcycle accident when he was 25.

The following year, Zhang rerouted an intercostal nerve from one side of

Huocheng’s body to the lumbar nerve roots and, in turn, an intercostal

nerve from the opposite side of his body to the sacral nerve roots.

These two nerve reroutings together restored much of  Huocheng’s

lower extremity function. For example, he now has considerable upper-leg

muscle control and

sensation down to his feet. Huocheng can now walk with crutches without

leg braces and has greatly improved bowel and bladder control.

Huocheng’s

lower extremity function. For example, he now has considerable upper-leg

muscle control and

sensation down to his feet. Huocheng can now walk with crutches without

leg braces and has greatly improved bowel and bladder control.

Follow-Up Case 2: In 1989, Bido became

injured in the lumbar region at age 17 after a car accident in Iceland.

After rehabilitation, she was able to walk using hip muscles in

conjunction with stiff braces that extended to her waist. Bido is the

daughter of Audur Gudjonsdottir, who was recently honored as Iceland’s

“Woman of the Year” for ongoing SCI advocacy efforts, including

spearheading the aforementioned WHO conference.

After

a facilitating request from Iceland’s President Vigdis Finnbogadottir,

Zhang traveled to Iceland in 1995 to surgically repair and remove scar

tissue from Bido’s spinal area. Audur, a nurse, indicated that so much

scar tissue was removed that “both of my hands were full of it.”

That operation alone restored some function. Audur believes that “each

individual who sustains SCI should have an operation like that some time

after the accident.” She adds: “as expected, the body attempts to

heal itself with scar tissue, which is a band aid. When the band aid is

removed and the pressure alleviated from the spinal cord or the nerve

roots, things begin to work again.”

After

a facilitating request from Iceland’s President Vigdis Finnbogadottir,

Zhang traveled to Iceland in 1995 to surgically repair and remove scar

tissue from Bido’s spinal area. Audur, a nurse, indicated that so much

scar tissue was removed that “both of my hands were full of it.”

That operation alone restored some function. Audur believes that “each

individual who sustains SCI should have an operation like that some time

after the accident.” She adds: “as expected, the body attempts to

heal itself with scar tissue, which is a band aid. When the band aid is

removed and the pressure alleviated from the spinal cord or the nerve

roots, things begin to work again.”

In 1996, Zhang returned to Iceland to reroute

Bido’s intercostal nerve to her lumbar nerve roots. As a result of

these surgeries, Bido’s ambulatory ability has greatly improved even

though the surgeries occurred many years after injury. According to

Audur, “Bido has motor function in both legs down to the ankles. As

such, she is now able to walk using braces that end below the knees. She

bends both knees during walking, and her balance is much better.”

Conclusion:

Increasingly, it seems that the most exciting SCI

therapeutic breakthroughs are originating in numerous places other than

America. Although American neuroscience is unrivaled, for a variety of

reasons - the pros and cons of which can be debated extensively - it has

been difficult to translate this scientific excellence into real-world

SCI therapies. Even when the initial scientific breakthrough happens in

America, the bench-to-bedside transfer of knowledge that transforms this

breakthrough into useful therapies often seems to occur elsewhere.

One potential reason has been implied by

Christopher Reeve, the well-known actor with SCI whose foundation

greatly contributes to and influences the nature of SCI research in this

country. Commenting on a peripheral nerve-routing operation carried by

Italy’s Brunelli, Reeve has stated “I think it is pretty immoral

because you have to follow a sequence. You’ve got to go from rats, a

lot of rats. Then you have to go to bigger animals, pigs hopefully, not

monkeys. You’ve got to demonstrate safety and efficacy.” (see

http://care cureatinfopop.com).

Reeve’s opinion reflects the prevailing

conservative approach of the American SCI research community, which

believes that serving its needs for scientific rigor is the best way to

serve the needs of people with SCI for new therapeutic options. However,

as someone who was extensively involved in setting SCI research

priorities in this community, I believe that the cows will come home a

long, long time before the pigs tell us anything truly useful.

Dr. Zhang’s peripheral-nerve-rerouting approaches

appear extraordinarily promising for restoring significant function

after SCI. In the spirit of

cooperation, we need to open-mindedly develop synergistic, mutually

beneficial collaborations that can evaluate innovative procedures such

as his and, more importantly, facilitate new understandings. One of

Zhang’s foremost desires is to see a professional exchange in which

his colleagues and their American counterparts would be able to visit

and learn from each other’s experience.

Society’s continued evolution into a “global

village” has allowed us to share technology so we can order a

comparable McDonalds Big Mac hamburger regardless of whether we are in

China or America. Given that we can share such culinary technology, it

would be an absurd sense of priorities not to be able to somehow share

SCI therapeutic knowledge that would benefit so many.

If we can bring together all the exciting SCI

developments throughout the world, restoration of function would no

longer be some distant pie-in-the-sky dream but a real-world expectation

now. It’s time to pull it all together. No more excuses. Let’s roll.

Acknowledgements & Resources: Special

thanks are extended to Dr. Shaocheng Zhang, his colleagues, and

superiors for extensive hospitality. Dr. Zhang can be reached by mail at

32-43-301, Zhongyuan Rd., Shanghai 200433, China or by fax at

001-86(country code)-21(city code)- 65346003.

For more-technical summaries

of Dr.

Zhang’s peripheral nerve rerouting procedures, click here.

For those who are potentially interested in this

peripheral nerve rerouting surgery, Zhang is willing to consider foreign

patients, who would stay in a modern foreign-guest clinic or is willing

to travel to America to carry out the surgery if an appropriate

collaborative relationship can be established with an U.S. hospital.

Adapted from article appearing in Paraplegia News, April, 2002 (For subscriptions, contact www.pn-magazine.com).