Experts have endorsed chiropractic as one of the most

effective ways of treating such pain, discouraging traditional approaches

of bed rest, medication, and surgery as counter productive. Most notably,

a 1997 U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy (AHCP) report stated,

“Chiropractic is now recognized as the principal source of one of the few

treatments recommended by national evidence-based guidelines for the

treatment of low-back pain, spinal manipulation.”

With 35-million Americans visiting 60,000

chiropractors each year, chiropractic is the nation’s third-largest

healthcare profession after medicine and dentistry. Of these people, 70%

use chiropractic for back pain; 25% for head, neck and extremity pain; and

5% for other disorders.

Due to its popularity, including among individuals

with physical disabilities, chiropractic should no longer be considered

“alternative medicine” but a key component of our healthcare system that

synergistically complements - not opposes - conventional medicine.

Chiropractic can help not only caregivers, who put

their backs in harm’s way, but, as discussed below, also enhance the

wellness of some people with spinal cord dysfunction and other

disabilities, whose wheelchair living (e.g., transfers, bad posture,

imbalanced muscle development, etc) aggravates physical problems amenable

to chiropractic treatment.

Definition:

Chiropractic focuses on diagnosing and treating

musculoskeletal disorders that affect the nervous system and, as a

consequence, general health. More specifically, the Association of

Chiropractic Colleges defines chiropractic as “A healthcare

discipline that emphasizes the inherent recuperative power of the body to

heal itself without the use of drugs or surgery. The practice of

chiropractic focuses on the relationship between structure (primarily

spine) and function (as coordinated by the nervous system) and how that

relationship affects the preservation and restoration of health. In

addition, doctors of chiropractic recognize the value and responsibility

of working in cooperation with other healthcare practitioners when in the

best interest of the patients.”

Chiropractic’s core philosophy differs from

conventional medicine, which believes we are the sum of our body parts

(e.g., organs, cells, or molecules); if we fix the parts, the body will be

repaired. In contrast, chiropractic grew out of a holistic vitalism

philosophy, which says that the body has an innate life force (e.g., like

qi or prana in Eastern-healing traditions) that flows down from the brain

with the nervous system and out from the spine to the periphery. Like

fixing a garden-hose kink, chiropractic adjusts musculoskeletal

distortions that inhibit this flow and, by so doing, enhances wellness.

History:

Chiropractic procedures have been a part of mankind’s

healing armamentarium since time immemorial, including use by ancient

Chinese, Egyptian, and Greek civilizations. Both Hippocrates (460-377

B.C.) and the influential Roman physician Galen (A.D. 129-199) recommended

vertebral adjustments to relieve ailments.

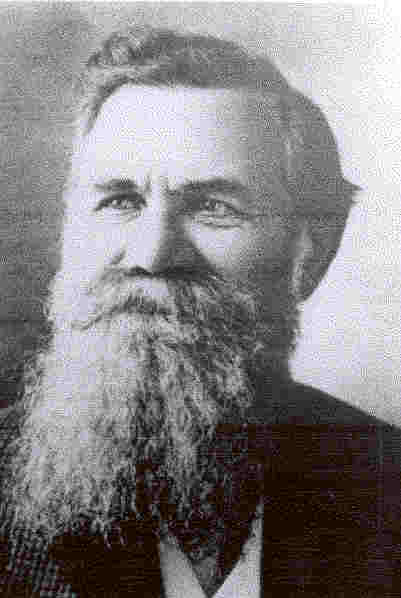

The f ounder

of today’s chiropractic was Daniel David Palmer (1845 –1913), a

self-educated man in medicine and science who practiced in Davenport,

Iowa. In 1895, through vertebral manipulation, he restored the hearing of

his building’s janitor, who had been deaf since a back accident 17 years

earlier. This incident gave birth to chiropractic, the term coined from

the Greek words praxis and cheir, meaning treatment by hand.

ounder

of today’s chiropractic was Daniel David Palmer (1845 –1913), a

self-educated man in medicine and science who practiced in Davenport,

Iowa. In 1895, through vertebral manipulation, he restored the hearing of

his building’s janitor, who had been deaf since a back accident 17 years

earlier. This incident gave birth to chiropractic, the term coined from

the Greek words praxis and cheir, meaning treatment by hand.

Much of the credit for chiropractic’s growth was due

to the organizational leadership of Palmer’s son Bartlett Joshua

(1881–1961), who at age 21 took over and built up the now well-known

Palmer School of Chiropractic in Davenport.

He

was an innovator, who, for example, integrated nascent x-ray technology

into the profession, and was an effective chiropractic promoter and

defender. He cultivated and lobbied national figures and U.S. presidents,

and even employed future President Ronald Reagan as a broadcaster at his

World of Chiropractic (WOC) radio station.

He

was an innovator, who, for example, integrated nascent x-ray technology

into the profession, and was an effective chiropractic promoter and

defender. He cultivated and lobbied national figures and U.S. presidents,

and even employed future President Ronald Reagan as a broadcaster at his

World of Chiropractic (WOC) radio station.

Gradually, states approved chiropractic; Minnesota

was the first (1905), and Louisiana the last (1974).

Chiropractic faced vociferous opposition from

organized medicine, which essentially viewed it as a threat to its

healthcare monopoly. Because medicine did not include a

spinal-manipulation focus - preferring its pharmaceutical and surgical

approaches - it minimized the benefits that could accrue from this focus

emphasized by a competing discipline.

In defense of organized medicine, which had made huge

healthcare advancements as it transitioned into the 20th

century and cleaned up its own house by imposing rigorous professional

standards, many of the early chiropractic profession’s actions,

infighting, lax standards fueled criticism. Chiropractic emergence was

also handicapped, however, because it did not advocate drugs, and, as

such, could not cultivate strong financial, pharmaceutical-industry

allies. (e.g., on average, every U.S. physician receives >$14,000 each

year from the pharmaceutical industry’s marketing and promotional

campaigns.)

Organized medicine was forced to back down when a

landmark, 1987 federal anti-trust ruling found the American Medical

Association (AMA) guilty of a prolonged and systematic attempt to

completely undermine the chiropractic profession, often using highly

dishonest methods. By stopping the major source of organized resistance,

this case ushered in a new era of cooperation between physicians and

chiropractors.

In recent decades, Federal actions have increasingly

supported chiropractic, including: the 1974 authorization to the Council

of Chiropractic Education to accredit schools, the aforementioned AHCP

endorsement of chiropractic to treat lower back pain, the 1996 decision by

the National Institutes of Health to fund chiropractic research, and

President Clinton’s 2000 mandate that chiropractic be made available to

all active-duty military personnel.

Education:

Facilitating its current acceptance, the chiropractic

profession has adopted strict educational standards, comparable in rigor

but different in focus from medical education. Although both professions’

basic-science components are equivalent in study time, chiropractic

emphasizes musculoskeletal and neuroanatomical systems over medicine’s

pharmacological and surgical priorities. Furthermore, in contrast to

medicine’s broad clinical preparation, chiropractic clinical training is

specialized, focusing on the profession’s unique diagnostic and treatment

methods, which can only be mastered through extensive, hands-on practice.

Procedures:

Chiropractors focus on correcting disordered

vertebral joints, which include vertebrae and their boney projections

(called facet joints and spinous or transverse process es),

shock-absorbing cartilage discs, muscles, ligaments, and nervous tissue. Subluxations

- abnormalities of this vertebral complex - affect health by impinging on

nerve roots as they exit the complex through channels called

intervertebral foramen.

es),

shock-absorbing cartilage discs, muscles, ligaments, and nervous tissue. Subluxations

- abnormalities of this vertebral complex - affect health by impinging on

nerve roots as they exit the complex through channels called

intervertebral foramen.

Because of the complex’s inherent intricacy,

subluxations can result from numerous, interacting factors that upset the

complex’s homeostatic equilibrium, e.g., from unbalanced muscle tension

that pulls a vertebra out of alignment with neighbors. In turn, a specific

subluxation can create a chain reaction affecting other parts of the

spinal column. For example, neck pain may be the secondary consequence of

a pelvic misalignment.

Chiropractic emphasizes non-invasive therapies, such

as manual treatments, physical therapy, exercise programs, nutritional

advice, orthotics, and lifestyle modification.

The most common procedure is the spinal adjustment,

accomplished through diverse techniques. For example, with spinal

manipulation, using the vertebral projections as levers, a carefully

measured force is rapidly applied to the joint that carries it past its

voluntary range of motion but still well within the range permitted by

nature. The commonly heard “crack” is actually a vacuum-created, nitrogen

bubble bursting within the joint. In contrast, with spinal mobilization

procedures, the joint remains within its passive range of movement.

Depending upon the problem’s acute or chronic nature,

often multiple treatment sessions are needed, 6-10 being the average.

Studies show that the chiropractic risks are minimal.

For example, a 1996 RAND Corporation study concluded that 1.5 serious

complications occur from every million cervical manipulations. For

comparison sake, there are 1,000 serious complications per million from

taking over-the-counter painkillers.

Chiropractic & Physical Disabilities:

People with disabilities frequently use chiropractic.

For example, a Kessler Institute (N.J.) study indicated 23% of people with

SCI with chronic pain had used chiropractic (Nayak et al, J. Spinal

Cord Medicine, Spring, 2001).

Dr. Julet Hutchens, a chiropractor

(photo) who practices with medical doctors

and physical therapists, discusses potential SCD benefits:

“I have treated patients with spinal cord dysfunction

for four years, the first of which was my husband Eddy, a wheelchair

athlete and Mountain States PVA associate member. When I met him, he had

been paralyzed 16 years due to an automobile accident, in which he

sustained a complete T-10 spinal-cord transection.

I adjust Eddy usually 1-2 times per month depending

on his activity and discomfort level. I keep the majority of my

adjustments to him and other paralyzed patients above the injury level.

However, occasionally, I will perform more passive types of mobilization

to the pelvis, low back, and lower extremities. Eddy says the adjustments

give him instant relief to shoulder problems, upper/mid-back and rib pain,

and neck pain. A Denver Rolling Nuggets basketball player, he recommends

chiropractic treatments to his teammates to ensure their continued full

range of movement above and below the injury site.

I often treat shoulder and rib-related injuries in individuals with

paralysis that result from their excessive shoulder and arm use associated

with frequent wheelchair transfers. Often, a repetitive-use injury occurs,

which, if not taken care of, can lead to more severe shoulder problems,

even requiring surgery. Chiropractic treats the shoulders and ribs, giving

the patient relief. And with any repetitive-use injury, strengthening

exercises reinforce adjustments, preventing future injuries.

As with any person sitting for long time periods, posture becomes an issue

in wheelchair users. Most end up with neck and upper-back pain due to bad

posture. When we sit for a long time, we tend to slump forward, placing

extra stress on the neck and upper back. When I observe wheelchair

athletes, I see them leaning forward, resting their arms on their legs, or

leaning slightly forward and to the side, resting on a wheel. Such posture

places extra stress on the neck and upper back, and, as a result, the

muscles around the spine become weak and those in the chest become

tighter. These changes cause an imbalance between front and back muscles,

which can lead to pain. I work with the patient to rebuild muscle balance,

and restore motion in the spine that is restricted from such imbalance.

Teaching patients the difference between good and bad posture is

especially important so that they become aware of the small changes they

can make to alleviate some of their neck and back issues.

Active individuals with paralysis will develop a strong upper body to

compensate for their inability to balance themselves through the use of

abdominal, leg, and lower-back muscles as an able-bodied person would.

Because of this upper-body reliance, we want to keep it in good working

order, which is accomplished through a strong chiropractic and stretching

and strengthening programs. Shoulder or neck pain can impair one’s ability

to not only transfer in or out of a wheelchair but also to push it,

limiting overall mobility.

Adjustments, muscle work, and exercises keep the spine, shoulders, ribs,

and shoulder blades moving as they should in a painless, full range of

motion. These methods keep the joints lubricated, discs between the

vertebrae from deteriorating, and muscles and ligaments strong and

balanced. At the same time, it loosens muscles.

Overall, because they will be healthier, feel better,

and have more energy, all wheelchair users should receive regular

bodywork.

When I treat patients with SCI, arthritis that causes joint fusing,

post-polio, or cerebral palsy, I adapt my treatment to accommodate the

patient. Depending on their disability, I treat patients in their

wheelchair, or if comfortable, I will help them transfer to a treatment

table.

I try to choose the optimal treatment for the

specific patient, some of which are more passive or aggressive than

others. I also x-ray all patients with SCI to see exactly what is going on

in their spine, shoulders, etc. With SCI, the body compensates in one

area for the lack of motion in another. Because such compensation can be

observed through x-rays, the patient can be more effectively treated.”

Chiropractic Restoration of Function?

Dr. Dudley Delany, a chiropractor, relates an

anecdotal case suggesting that chiropractic therapy may have the potential

to restore some function after SCI. Specifically, when Delany was a

freshman chiropractic student, the school's president indicated that he

had became a paraplegic after a football injury but was able to regain

full recovery through chiropractic spinal manipulations. For further specifics,

see

http://www.webspawner.com/users/chiroscitx/index.html

Conclusion:

Most healing traditions have something valuable to

offer yet, at the same time, have limitations in scope. Allopathic

medicine emphasizes valuable pharmaceutical and surgical interventions,

chiropractic focuses on musculoskeletal system mechanisms that medicine

has ignored, and other traditions stress different therapeutic concepts

and modalities that also have great validity. It is as if medicine looks

at the world through red-tinted lenses, chiropractic blue lenses, and

other disciplines green or other colored lenses.

Unless we work together more in unity than

opposition, each discipline’s vision will remain inherently limited to the

detriment of all. However, if we open-mindedly accommodate divergent views

of what is possible, we create an expanded healing spectrum that will

benefit all, including those with spinal cord dysfunction.

Contact: Dr. Julet Hutchens, CLINIX, 7030 S.

Yosemite, Centennial, CO 80116 (303-721-9984).

Adapted from a two-part article appearing in Paraplegia News,

October & November, 2003 (For subscriptions, contact www.pn-magazine.com).

TOP