In recent years, a variety of aggressive physical

rehabilitation programs have emerged that seem to restore significant

function for many people after spinal cord injury (SCI), even years after

injury. This article discusses several of the programs, as well as key

issues surrounding their use.

Introduction

Increasingly, such aggressive rehabilitation is being

used to maximize restored function after cell-transplantation or other

innovative surgeries that are surfacing throughout the world, including

those discussed in previous articles. Often videos are produced to

document improvement, and given the impressive nature of the physical

activities that could be done after but not before surgery, it is assumed

that the new-found abilities prove the intervention’s efficacy.

However, this assumption may not be valid; in fact,

in some cases, perhaps little of the restored function is due to the

surgery but rather to the rehabilitation aggressively pursued after

the intervention but not before. If post-surgical functional recovery

depends upon slowly regenerating neurons reaching an anatomically distant

target site, it will take a relatively long time for improvements to

appear. If during that period, the patient is enthusiastically working

out, the true cause of any ensuing improvement is questionable. As such,

some surgical interventions now require patients to aggressively

rehabilitate before, as well as after, surgery.

Furthermore, if patients believe with heart-and-soul

conviction that the surgery will help him, it will shift their

consciousness from the prior “you-will-never-walk-again” attitude that is

often imprinted on the patient’s consciousness by our medical authorities

to a self-fulfilling belief of what may be truly possible through hard

work. Their will propels them to new functional levels, perhaps only a

small amount of which is actually due to the surgery.

Even by itself, aggressive physical rehabilitation is

a complicated area in which improvements may be due to many causes and

mediating physiological mechanisms. First, such rehabilitation most likely

stimulates some function-restoring neuronal regeneration, adaptation,

and/or reconfiguration (i.e., plasticity); and also may activate dormant

but intact neurons that transverse most injury sites, even injuries

clinically classified as complete. Studies suggest that only a small

percentage of “turned-on” neurons are needed to regain significant

function.

Second, the spinal cord by itself possesses

intelligence and is not completely subservient to brain oversight.

Specifically, the spinal-cord’s “central-pattern generator” can sustain

lower-limb repetitive movement, such as walking, independent of direct

brain control. With training and braces, impressive ambulation may be

observed through physically stimulating this neural network.

Third, many muscles above the injury site indirectly

affect ambulation, especially through the use of leg braces. For example,

the latissimus dorsi (i.e., the lats), which are innervated from the

cord’s cervical region, influence pelvic-area movement and, in turn,

ambulation.

Fourth, aggressive physical rehabilitation is often

initiated in the first year after injury, a period in which appreciable

recovery potential exists. As such, critics have suggested that any

functional recovery, no matter how dramatic, would have happened anyway.

Finally, in paradigm-expanding speculations, experts

knowledgeable in Eastern and esoteric-healing traditions believe that it

is possible for brain-directed function below an anatomically complete

injury site. Specifically, a sophisticated interaction takes place between

our body’s electromagnetic energy meridians, systems, and fields and

neurological systems that can bypass the injury site. As such, it has been

suggested that martial-arts or qigong study, which emphasize energy-flow

and control, facilitates this potential.

Summaries are provided below on various aggressive,

function-restoring rehabilitation programs:

Neuro Institute

Arnie Fonseca was the driving force behind the

creation of the Neuro Institute in Tempe, Arizona (www.theneuroinstitute.com).

An exercise physiologist and former coach, Fonseca motivates clients with

SCI and other neurological disorders to regain sometimes amazing function.

I met Fonseca and was impressed with his drive, can-do spirit, and

commitment to his rehabilitation mission, which became personal after his

son Brandon sustained a serious head injury from an auto accident.

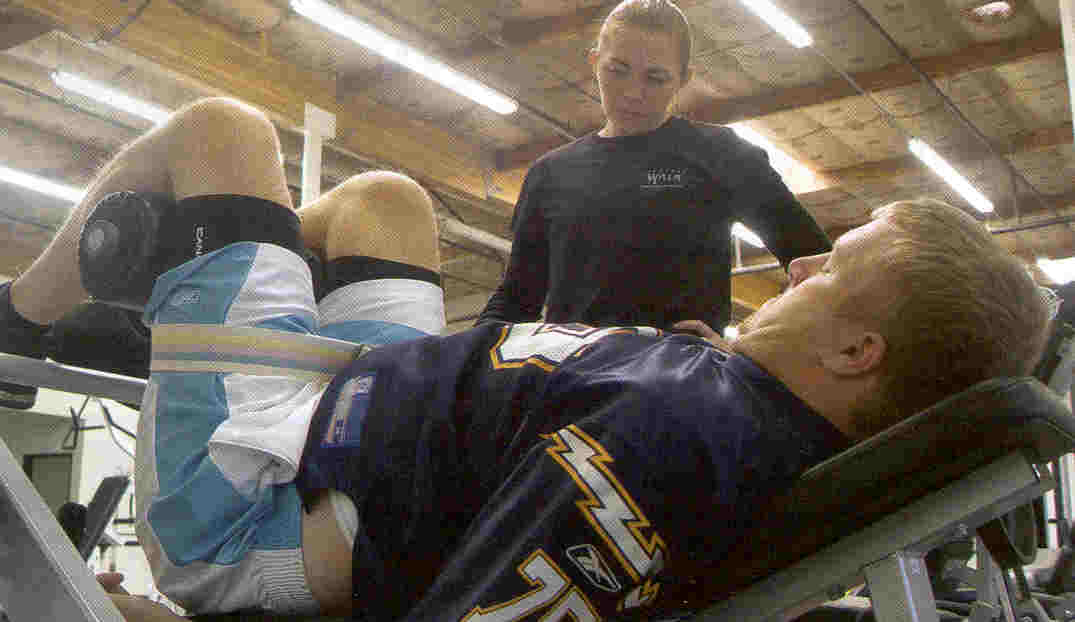

(Photo: Arnie and Cari Fonseca, with son Brandon, co-founded the Neuro

Institute)

Fonseca describes his program as immersion therapy.

He believes that the best way for a neurologically compromised patient to

get positive results is to be immersed in goal-oriented rehabilitation

therapy for at least three hours a day for 3-5 days a week. There is no

magic technique; the program uses a variety of rehabilitation approaches

ranging from electronic equipment (e.g., FES bikes) to old-fashioned,

low-tech weight training. Through his “just-do-it” motivational prowess,

Fonseca encourages patients to replace entrenched defeatist attitudes with

a new conviction of what is possible if they work hard.

Several impressive success stories are documented on

his Web site. One of the more notable involves Andrea, whose experience

represents a good example of how function-restoring surgeries are being

combined with aggressive rehabilitation. Briefly, an

omental/collagen bridge was used to bridge a 4-cm gap in Andrea’s cord

that resulted from a skiing accident (see Neurological Research 27,

2005). Since starting Fonseca’s program, Andrea regained considerable

function, including some ambulation. Time-sequential MRIs indicate ongoing

development of axonal structure through the once huge, spinal-cord gap.

Although we cannot distinguish surgical from rehabilitation contributions,

this is the sort of synergistic programs that we are going to see much

more of in the future.

Project Walk

Many people with SCI who have committed to Project

Walk (www.projectwalk.org) have accrued function much beyond what was

considered possible after injury. The intensive exercise-based recovery

program, developed by Ted and Tammy Dardzinksi in Carlsbad, California,

attempts to re-educate the damaged nervous system through physical

stimulation. Because each injured system is unique and each patient has

different capabilities, the program is tailored to individual clients.

Briefly, Project Walk focuses on developing muscle

potential below the injury level. The Dardzinksis believe standard

rehabilitation programs not only ignore this potential but contribute to

its extinction by “tossing-in-the-towel” focusing on non-paralyzed body

parts needed for adaptation to wheelchair living instead of ambulation.

They also believe the extensively administered

anti-spasticity medications are the equivalent of pouring water on the

flickering embers of regeneration that often still exist after injury. In

contrast, Project Walk’s goal is to fan these embers into a phoenix-like

reemergence of functionality.

Underscoring their reservations with prevailing

rehabilitation thinking, the Dardzinksis note: “If

you were to place an able-bodied person in a reduced gravity environment,

tell them they can’t move for a year, heavily medicate them, and give them

no hope, what do you think the outcome would be? Bone density, muscle

mass, and nervous system activity would begin to shut down and disappear.

That able-bodied person would have the same symptoms of a paralyzed

person. So, is it just the injury or the treatment that keep some SCI

paralyzed?”

Believing there is a post-injury therapeutic window

in which the recovery potential is greatest, Project Walk ideally would

like to start treating patients relatively soon after injury. The program

believes that without proper stimulation and load bearing, a newly injured

person will soon start losing bone density, muscle mass, and CNS

functioning, which makes future recovery even more difficult. Although the

program has treated many after this window, sometimes with dramatic

improvements, much more effort is needed.

Although the training schedule depends upon a

person’s function, the average client works out three hours every other

day. For people returning home, individually tailored, home-based

programs are designed. Although intensive, the program encourages clients

not to embrace it exclusively at the expense of overall life balance

achieved through involvement in areas such as career, school, social life,

etc.

The program combines strengthening activities for all

muscles in the extremities and core (abdominal, back, and pelvic), balance

work, and coordination drills. Exercises are structured to activate

paralyzed areas and strengthen weak muscles. Specialists facilitate active

and passive motions in various planes of motion to reactivate and

reorganize the nervous system. This includes floor exercises, assisted or

unassisted work on Total Gyms®, and body-weight-supported

ambulation. The common component is weight bearing through the body’s long

bones.

Functional improvements include increased muscle

mass, CNS activity, health and well being, sensation and function below

the injury level, occupational skills, and sweating, as well as decreased

drug dependence and pain.

Project Walk encourages the use of synergistic

healing modalities, including acupuncture, hyperbaric oxygen therapy,

standing frames, FES bikes, and other electrical stimulation that helps to

maintain muscle mass and circulation; and emphasizes good nutrition.

Additional aggressive physical rehabilitation

programs will be discussed in Part 2.

Adapted from article appearing in February 2006 Paraplegia News (For subscriptions,

call 602-224-0500) or go to www.pn-magazine.com).

TOP