Part 1 discussed key characteristics of

Native-American medicine. It focused on the paramount role of spirit,

including not only in the patient but also the healer, family, community,

environment, and medicine, and the dynamics between these forces as a part

of the Universal Spirit.

Part 2 summarizes specific healing modalities, some

of which can be understood, at least superficially, through conventional

biological mechanisms (e.g., herbal remedies) and others that must be

understood, once again, within a greater spiritual context.

Basically, the

fundamental goal of all Native-American healing is to est ablish a better

spiritual equilibrium between patients and their universe, which, in turn,

translates into physical and mental health. [Photo: Rock art (Utah)

of medicine person with large eyes and snake spirit helper.]

ablish a better

spiritual equilibrium between patients and their universe, which, in turn,

translates into physical and mental health. [Photo: Rock art (Utah)

of medicine person with large eyes and snake spirit helper.]

Medicine is Spirit

Marilyn Youngbird (Arikara and Hidatsa Nations), an

international lecturer on native wisdom and former Colorado Commissioner

for Indian Affairs, emphasized Spirit’s overriding role to me: “It is

difficult for the average American, who thinks medicine is merely

swallowing a pill, to understand that medicine does not live outside of

us. Medicine is a part of Spirit that exists in, animates, and connects

all of us. Spirit is life, and its healing energy is available to

us if we learn to know, live, breathe, walk, and speak it.”

Native-American Disability

Eighteenth-century records suggest that paralysis was

rare among Native Americans before contact with whites. Today, however,

their SCI incidence is two-four times that of whites because they face

more of modern society’s injury-aggravating downside (primarily mediated

through motor vehicle accidents) combined with the historical suppression

of mitigating cultural support systems.

Native Americans traditionally believed that a person

weak in body is strong in mind and spirit. According to The Native

Americans (2001), such conviction is “related to the all-pervasive

regard for differences…the curtailing of some ability, whether physical or

mental, was more than compensated for by some special gift at

storytelling, herbal cures, tool-making, oratory, or putting people at

ease.”

Traditionally, Native Americans thought that many

inherited disorders are caused by parents’ unhealthy or immoral behavior

(fetal alcohol syndrome would be a good example in today’s world). The

Delaware and other tribes believed paralysis results from a patient or

parent taboo breach, and the Comanche called it a “ghost sickness” created

by negative spirits or sorcery. Because some diseases or disorders are the

result of the patient’s behavior, treatment may interfere with important

life lessons.

Healing Approaches

Because it is difficult to succinctly summarize a

subject as involved as Native-American medicine and do it justice,

interested readers are encouraged to review Honoring the Medicine

(2003) by Kenneth “Bear Hawk” Cohen (adopted Cree Nation), selected as the

National MS Society Wellness Book of the Year.

Plants

Because of Native Americans’ intimate relationship

with nature, many therapies emphasize plants’ mind-body-spirit healing

potential.

Herbs: Native-American herbalism is much more

complex than herbs merely serving as a plant matrix to deliver

physiologically active chemicals. First, because numerous plant components

affect bodily functions and bioavailability, the entire remedy is

considered the active agent. Second, because plants are believed to

possess spirit and intelligence, they are consulted to determine their

best healing relationship with patients, and permission is obtained before

and gratitude expressed after harvesting them. Third, intricate

procedures are used to harvest herbs, considering factors such as plant

part (e.g., flower, stem, root, etc), time or season of harvesting, sun

exposure, and much more obscure factors. Fourth, native herbalists use

plants that appear in dreams, a form of communication by which the plant’s

spirit can guide the healer. Finally, the plant’s healing potential is

empowered by ritual ceremony, prayer, song, or chants. Cohen notes that

although herbs can treat symptoms without such empowerment, they will not

reach the deeper causes of illness.

Tobacco: Ironically, the most spiritually

powerful plant is tobacco, modern society’s substance of greatest abuse.

Tobacco is the herb of prayer, placed on earth by spirits to help us

communicate with them and nature. All tobacco use, ranging from ceremonial

to cigarettes, should be treated with respect and awareness. Specifically,

the famous elder Rolling Thunder (Cherokee) taught Cohen: “After you light

tobacco, with your first puff, you should think a good thought or make a

prayer. With your second, quiet your mind; rest in stillness. With your

third puff, you can receive insight related to your prayer – perhaps an

image, words spoken by spirit, or an intuitive feeling.”

Smudge: Other sacred plants are used for

smudging, a purification procedure in which a plant’s aromatic smoke

cleanses an area of negative energies, thoughts, feelings, and spirits.

Smudging is a key component of healing prayers and ceremonies. The most c ommonly

used plants are sage (not the food spice) and cedar, which drive out

negative energy, and sweetgrass, which invites in positive, healing

spirits. Cohen believes that all healers should smudge between clients to

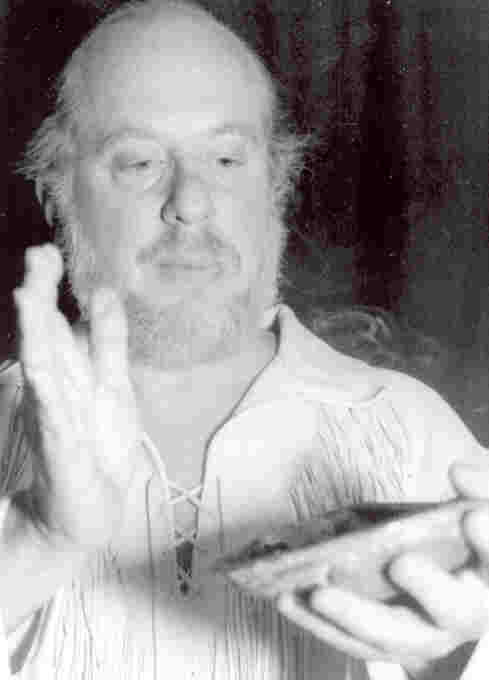

prevent the transfer of pathogenic energy. [photo:

Cohen smudging from shell]

ommonly

used plants are sage (not the food spice) and cedar, which drive out

negative energy, and sweetgrass, which invites in positive, healing

spirits. Cohen believes that all healers should smudge between clients to

prevent the transfer of pathogenic energy. [photo:

Cohen smudging from shell]

Prayer, Chants, and Music

Prayer is pervasive in Native-American healing. As

reviewed previously in this “Healing Option” series, substantial

scientific evidence exists that prayer can affect health. As Cohen notes,

Native-American prayer concentrates the mind on healing, promotes

health-enhancing emotions and feelings, and connects people to sacred

healing forces. In contrast to more familiar whispered prayers, Native

Americans robustly proclaim, chant, or sing prayers. Singing is often

accompanied by drumming or rattles, which, by synchronizing group

consciousness, greatly magnifies healing impact.

Lewis Mehl-Madrona (Cherokee), an emergency-room

physician and author of Coyote Medicine (1997), told me that prayer

should be incorporated into overall therapy after any major injury: “At

the time of acute injury, enroll everyone - patient, family members,

friends, doctors, nurses - in a prayer circle with the expectation of the

best outcome.”

Therapeutic Touch & Energy Work

Native-American medicine includes many approaches

with similarities to today’s alternative bodywork or energy-related

techniques, including massage, therapeutic touch, and acupressure-like

stimulation of body points.

Counseling

Counseling helps patients find a more

health-promoting, mind-body-spirit balance through, for example,

developing a better understanding of a life path and purpose or the role

that the disease or disorder plays. Because the counseling is based on

spiritual wisdom, Cohen likens it more to pastoral counseling than

psychotherapy.

Ceremony

Native-American ceremonies incorporate a variety of

healing modalities into a ritualized context for seeking spiritual

guidance. According to Cohen, one of the ceremony’s chief goals is

communicating with the spirit of a disease to gather information that can

lead to the release of pathogenic forces.

Mehl-Madrona indicated to me “at one time in their

history, all cultures have had beneficial healing ceremonies;

unfortunately, most modern, white-culture ceremonies have become so

sterile they are not conducive for healing.”

I recently participated in a sweat-lodge ceremony in

the traditional Lakota style. It was held in a dome-like structure covered

by tarps and heated by pouring water over hot stones (the stone people).

Tobacco prayer ties were hung inside, smudging herbs sprinkled on the

stones, and sacred pipes ceremonially smoked. Participants prayed, sang,

and chanted to obtain guidance, wisdom, and healing not only for

themselves but for all who are a part of Mother Earth’s greater unity.

Overall, the sweat-lodge’s

mind-body-spirit-purification, communion-with-spirit process helps people

understand who they are, especially relative to any disease or disorder.

With such empowering understanding, you start reclaiming responsibility

for and taking charge of your own soul rather than relinquishing its

direction to healthcare authorities.

Because the sweat lodge is totally dark except for

the faint glow of hot stones, no one has a disability in the ceremony;

everyone is an equal participant. The ceremony can target underlying

emotional causes of substance abuse, a problem that plagues many with SCI.

It can also promote healing at different levels by generating forgiveness,

releasing bitterness, and busting apart the self-fulfilling belief pattern

that is imprinted onto most patients after injury that they will never

walk again. (Because the sweat lodge is, indeed, hot, it is not

recommended for those with higher level, sweat-inhibiting injuries.)

Based on Native-American values and beliefs,

Mehl-Madrona developed a ceremony-emphasizing program that targets

non-natives with chronic disease or disorders. In the professional journal

Alternative Therapies (January 1999), Mehl-Madrona reported that

more than 80% of program enrollees accrued significant, persistent

benefits.

A Case Study:

The following case study illustrates many of the

previously discussed approaches. Specifically, Cohen used Si Si Wiss

healing - an intertribal tradition from the Puget Sound area - to restore

ambulatory function in Jon, an Icelandic man with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Due to chronic knee pain, Jon could not place his full weight on his left

leg and could only walk short distances using a walker. (see American

Indian Healing in the Land of Fire and Ice posted on

www.wholistichealingresearch.com).

Cohen believes that location played a key role in

Jon’s healing. Native Americans believe that certain geographical

locations possess strong healing energy (among Christians, the most

well-known such site is Lourdes, France). Cohen was lecturing near

Iceland’s Snæfellsnes Glacier, a legendary Nordic sacred area that author

Jules Verne chose for his intrepid explorers to start their descent in

Journey to the Center of the Earth.

From his audience, Cohen recruited participants for a

healing circle that surrounded Jon and instructed them to sing a healing

song to a drum beat.

Cohen relates: “I cleansed Jon with a smudge of local

bearberry leaves and juniper. As I waved the smoke around his body with my

hands, I also imagined that Grandmother Ocean (within view) was purifying

him. I then placed my hands on Jon's spine, one palm at his sacrum, the

other above his seventh cervical vertebrae. I rested my palms there for a

few minutes, to both "read" the energy in his spine and to focus healing

and loving power.”

“I then held his knee lightly between my two palms,

focusing with the same intent. After this, I did non-contact treatment,

primarily over Jon's head, focusing on the brain itself. I held my hands a

few inches from his skull, one hand in front, one in back, then one hand

to the left, one to the right. I continued, holding my palms above his

spine, moving them gently up from the sacrum towards the crown and then

down the front mid-line of his body.”

As I continued with non-contact treatment, I prayed

in a soft voice, yet loud enough for Jon to hear me, and with a tone,

rhythm, and intensity that harmonized with the sound of the background

singing and drumming. … "Oh Creator, I ask for healing for this brother.

Let him learn his lessons through your guidance and wisdom, not through

pain. I pray that whether this condition was caused by inner or outside

forces, whether originating from this time or any time in the past,

whether intentionally caused by offended people or spirits or caused by

chance-- let the pain and disability be lifted and released in a good and

natural way."

At the ceremony’s end, “I helped him to stand and was

about to move his walker over to him, when he said, "No, wait a moment. I

feel something." He began to walk without assistance, slowly but with an

apparently normal gait. He showed no sign of unsteadiness and was able to

use his left leg easily. I walked along side of Jon, expecting him to lose

balance and fall. Instead, he turned towards me, embraced me and said,

tearfully, "Thank God! It's a miracle. I can walk!"

Residents of Jon’s village, who had known him for

many years, later expressed their amazement to Cohen of seeing Jon walking

about town normally.

Cohen’s treatment included therapeutic energy work.

As such, it should be noted that his ability to transfer electromagnetic

energy through intention, with and without direct touch, has been

documented in rigorous experiments at the prestigious Menninger Clinic,

Kansas. Because of his reputation, many of his patients have, in fact,

been referred to him by physicians.

Conclusion:

The study of Native-American and other indigenous

healing traditions is important because they have greatly influenced

modern medicine in spite of major philosophical differences; collectively

still play a huge global healthcare role; and offer solutions to modern

society’s ailments that our spiritually-bereft science cannot.

Native Americans believe their actions must consider

the welfare of the seventh generation to come. Perhaps this is why their

ancient wisdom is not just intriguing anthropological residuum pushed

aside by Western civilization but re-emerging in relevance to the present

generation.

Acknowledgements: The author expresses

gratitude for all his teachers of native wisdom, especially Kenneth Cohen.

Adapted from article appearing in Paraplegia News,

October 2004 (For subscriptions,

go to www.pn-magazine.com).