As part of this ongoing series, I have reviewed

diverse healing approaches, none of which has been more intriguing yet

initially alien to my Western-trained scientific mind than Native-American

medicine. As a scientist who uses physical laws to further dissect the

microcosm, it was challenging to metaphorically absorb the spiritual,

cosmological, and ecological views of the macrocosm that shape

Native-American healing.

In The Way of the Scout: A Native American Path to

Finding Spiritual Meaning in a Physical World (1995), Tom Brown, Jr.

describes how when he was a child an Apache elder taught him to use an

“expanded focus,” where the task (i.e., any of life’s pursuits) is but a

small part of the whole picture. When we relax an absolute focus, we

become more aware of life’s flow around us, and, as a result, assistance

in many unanticipated forms becomes available.

For most of us who view the world through the

conditioning of Western thought, an expanded focus fosters a greater

understanding of Native-American wisdom. In my case, as I relaxed the

rigidity of my scientific beliefs, an understanding grew that complemented

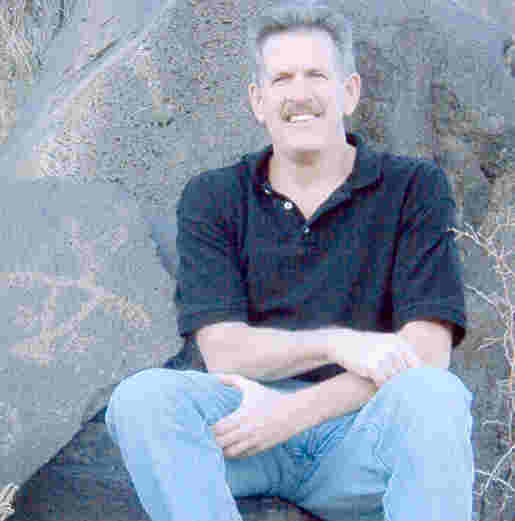

- not negated - these beliefs. (photo: The author next to a petroglyph of “Thunderbird,” a

mythological being who speaks in thunder and lightening and teaches us how

to use its power to heal.)

The author next to a petroglyph of “Thunderbird,” a

mythological being who speaks in thunder and lightening and teaches us how

to use its power to heal.)

Contributions:

Throughout our nation’s history, Native-American

societal contributions have been immense but often unrecognized. A few

examples include Benjamin Franklin’s modeling the Articles of

Confederation on the Iroquois Nation’s constitution, World War II’s Navajo

code breakers, tribal donations of over $200,000 for post-9/11 relief

efforts, and, the first servicewoman killed in Iraq being a Hopi Indian.

Such contributions hold true for medicine, also. For

example, more than 200 Native-American herbal medicines have been listed

at one time or another in the US Pharmacopoeia; many modern drugs have

botanical origins in these medicines.

Indigenous Medicine:

Native-American medicine is classified as an

indigenous healing tradition. Because 80% of the World’s population cannot

afford Western high-tech medicine, indigenous traditions collectively play

an important global healthcare role - so much so that the World Health

Organization recommended that they be integrated into national healthcare

policies and programs.

Although Native-American healing reflects the

diversity of the many Native nations or tribes that have inhabited “Turtle

Island” (i.e., North America), common themes exist not only between them

but with many of the World’s geographically diverse, ancient indigenous

traditions.

Role of Spirit & Connection:

A major difference between Native-American and

conventional medicine concerns the role of spirit and connection. Although

spirituality has been a key component of healing through most of mankind’s

history, modern medicine eschews it, embracing a mechanistic view of the

body fixable pursuant to physical laws of science.

In contrast, Native-American medicine considers

spirit, whose life-force manifestation in humans is called, ni by

the Lakota and nilch’i by the Navajo, an inseparable element of

healing. Not only is the patient’s spirit important but the spirit of the

healer, the patient’s family, community, and environment, and the

medicine, itself. More importantly, healing must take in account the

dynamics between these spiritual forces as a part of the universal spirit.

Instead of modern medicine’s view of separation that

focuses on fixing unique body parts in distinct individuals separate from

each other and the environment, Native Americans believe we are all

synergistically part of a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts;

healing must be consider within this context. Specifically, we are all

connected at some level to each other, Mother Earth (i.e., nature), Father

Sky, and all of life through the Creator (Iroquois), Great

Spirit (Lakota), Great Mystery (Ojibway), or Maker of All

Things Above (Crow).

This sense of wholeness and connection is implied by

the concluding phrase of healing prayers and chants “All my Relations,”

which dedicates these invocations to all physical and spiritual relations

that are a part of the Great Spirit. To metaphorically describe our

universal connection, the Lakota use the phrase mitakuye oyasin –

“We are all related,” while Southwest pueblo tribes, who consider corn as

a life symbol, state “We are all kernels on the same corncob.”

In Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence

(2000), Dr. Gregory Cajete uses modern science’s chaos theory to

support the Native-American concept of connection. Sometimes called the

“butterfly effect,” this theory postulates that a butterfly’s wing

flap may initiate a disturbance that ultimately leads to a hurricane or

another phenomenon across the world. Whether it is this flap, a prayer for

healing, or one’s stand against oppression, chaos theory, as well as

Native American philosophy, implies that everything is related and has an

influence no matter how small.

Moreover, we all have “butterfly power” to create

from the inherent chaos of our universe, which Cajete describes as “not

simply a collection of objects, but rather a dynamic, ever-flowing river

of creation inseparable from our own perceptions.”

Cultural Rebirth:

Although you cannot appreciate Native-American

medicine without its spiritual dynamics, surprisingly, the practice of

Native-American spirituality was banned in the land of religious freedom

until the 1978 passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. For

example, in Coyote Medicine: Lessons from Native American Healing

(1997), Dr. Lewis Mehl-Madrona tells how he risked jail for attending an

early 1970’s healing ceremony.

Because of this ban, which forbid congregating and

keeping sacred objects, much of Native-American healing was driven

underground or to extinction. It is the equivalent of telling physicians

they can’t practice medicine if they do surgeries or prescribe drugs.

Since the prohibition’s lifting, however, world-wide interest in

Native-American wisdom has soared, in part, because it is perceived as an

antidote to modern society’s soul-depleting and environment-damaging

aspects.

Disability:

The idea of wholeness is paramount in understanding

Native-American perception of disability. Unlike many cultures that shun

people with disabilities, Native Americans honor and respect them. They

believe that a person weak in body is often blessed by the Creator as

being especially strong in mind and spirit. By reducing our emphasis on

the physical, which promotes our view of separation from our fellow man

and all that is, a greater sense of connection with the whole is created,

the ultimate source of strength.

Overall, in treating physical disability,

Native-American healers emphasize quality of life, getting more in touch

with and honoring inherent gifts, adjusting one’s mindset, and learning

new tools. By so doing, the individual’s humanity is optimized.

Distinguishing Features

In addition to these overarching philosophical

differences, there are many other features that distinguish

Native-American from Western medicine. In Honoring the Medicine: The

Essential Guide to Native American Healing (2003), selected as the

National MS Society Wellness Book of the Year, Kenneth “Bear Hawk” Cohen

summarizes some of them in a table (p 307):