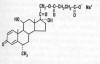

Methylprednisolone (MP) is a glucocorticoid steroid

(illustration) administered soon after spinal cord injury (SCI) in an

effort to minimize neurological damage. If you have sustained a SCI over

the past dozen years or so, you were probably treated with this drug.

Although it has become a de facto post-injury standard of care in

the U.S., many scientists are challenging MP’s effectiveness and

underlying scientific foundation.

MP Studies

Extensive animal research suggests MP reduces

post-injury neurological damage, in part, by inhibiting lipid

peroxidation, a biochemical process that mediates secondary damage to

the injured cord. A number of large MP-focused clinical trials have been

conducted, including the National Acute SCI Study (NASCIS) 1, 2, and 3.

In the NASCIS-2 study (NASCIS 1 generated no

significant results), 162 acutely injured patients received a high MP

dose consisting of an initial bolus of 30 milligrams (mg) per kilogram

(1 kg) of body weight. This was followed by infusion of 5.4 mg/kg/hour

for 23 hours. The patients were compared to 171 subjects given an

inactive placebo. Motor and sensory function was assessed at admission,

after six weeks, and after six months. Investigators concluded that

patients treated with MP within eight hours of injury had improved

neurological recovery.

Before the results were published, the National

Institutes of Health (NIH) disseminated them through announcements and

faxes to emergency-room physicians and the news media. Though this was

done to help newly injured patients as soon as possible, it essentially

created a standard of care before other experts could critically

evaluate the results.

In NASCIS 3, after receiving the same initial MP

dose within eight hours of injury, 499 acutely injured subjects were

randomized to receive the same rate of MP infusion as described above

for 24 or 48 hours (a third of patients received another drug).

Follow-up assessments were again carried out at six weeks and six

months. The investigators concluded that if MP is initially

administered within three hours of injury, the regimen should be

continued for 24 hours; if initiated three to eight hours after injury,

the regimen should be continued for 48 hours.

MP’s side effects included gastrointestinal

bleeding, wound infections, and delayed healing. The

NASCIS studies and other smaller studies suggest an increased incidence

of sepsis (blood-stream infection) and pneumonia in the MP-treatment

groups.

Critics

Reflecting Mark Twain’s statement “There are three

kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” many critics believe

that MP has been promoted as a standard of care for acute SCI based on

results generated through the use of questionable statistical

procedures. These doubters claim that NASCIS showed little if any

statistically significant benefits from high-dose MP, and modest

benefits were only demonstrated in a patient subgroup when data was

later micro-analyzed.

This controversy is not insignificant. For example,

a survey of participants at a 2001 Annual Canadian Spine Society meeting

indicated “75% of respondents were using MP either because everyone else

does or out of fear for failing do so.”

This society and the Canadian Neurosurgical Society

commissioned an expert review of the available MP data, which concluded

that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of MP as a

treatment standard or guideline, although weak clinical evidence

supports its use as a treatment option.

Other articles challenging MP’s use include:

1) Dr. Shanker Nesathurai (Boston) said that

neither NASCIS 2 nor 3 convincingly demonstrated MP’s benefits (J

Trauma 1998; 45[6]). “There are concerns about the statistical

analysis, randomization, and clinical benefits… Furthermore, the

benefits of this intervention may not warrant the possible risks.”

2) Dr. Deborah Short and colleagues (U.K.)

concluded: “The evidence produced...does not support the use of

high-dose methylpredinisolone in acute spinal-cord injury to improve

neurological recovery. A deleterious effect on early mortality and

morbidity cannot be excluded by this evidence.” (Spinal Cord,

2000; 38[5])

3) Dr. W.P. Coleman et al (Annapolis Md) strongly

criticized both NASCIS 2 and 3 for methodological weaknesses and the

lack of data that could be critically reviewed by others (J Spinal

Disord 2000; 13[3]). For example, they stated: “The

numbers, tables, and figures in the published reports are scant and are

inconsistently defined, making it impossible even for professional

statisticians to duplicate the analyses, to guess the effect of changes

in assumptions, or to supply the missing parts of the picture.

Nonetheless, even 9 years after NASCIS II, the primary data have not

been made public…These shortcomings have denied physicians the chance to

use confidently a drug that many were enthusiastic about and has left

them in an intolerably ambiguous position in their therapeutic choices,

in their legal exposure, and in their ability to perform further

research to help their patients.”

4) Dr. R.J. Hurlbert (Alberta, Canada) concluded:

“The use of methylprednisolone administration

in the treatment of acute SCI is not proven as a standard of care, nor

can it be considered a recommended treatment. Evidence of the drug's

efficacy and impact is weak and may only represent random events. In the

strictest sense, 24-hour administration of methylprednisolone must still

be considered experimental for use in clinical SCI. Forty-eight-hour

therapy is not recommended.” (J Neurosurg 2000; 93[1 suppl])

5) Dr. Tie Qian and colleagues (Newark, NJ)

suggested that high-dose MP may damage muscles through acute

corticosteroid myopathy (ACM) and that functional improvement attributed

to MP may merely be due to the recovery of muscle damage caused by this

extremely high MP dose (Med Hypothesis 2000; 55[5]). The

investigators noted that under the NASCIS 3 clinical protocol, a 75-kg

(165 pounds) acutely injured individual could receive nearly 22 grams of

MP, which is the “highest dose of steroids during a 2-day period for any

clinical condition.”

This is, indeed, a strong indictment. As a crude

analogy, consider this: I punch you forcefully in the arm and create a

bad bruise. I then claimed that the healing of the bruise was due to -

and not caused by - the punch. In this analogy, MP is the punch.

6) Further investigating this issue, Qian and

colleagues (Miami, Fla) compared five acutely injured patients who

received high-dose MP regimen with three control patients, who did not

meet the requirements for MP treatment (specifically, two gunshot

injuries and one who arrived at hospital too late) (Spinal Cord

2005; 43[4]). Muscle damage was assessed by biopsy and electromyography

(EMG - measures the amount of conduction signal reaching the muscle).

The biopsies and EMG data indicated that four of the five MP-treated,

but no control, patients had muscle damage consistent with ACM. The

investigators concluded that “the improvement of neurological recovery

showed in NASCIS may be only a recording of the natural recovery of ACM,

instead of any protection that MP offers to the injured spinal cord.”

Conclusion

Because I was a NIH division director when the

agency promulgated its MP-treatment policy, I know that it was a

conscientious decision in an effort to help those with acute injuries.

Unfortunately, we may have to revisit the policy, which could be

difficult given that changing the direction of entrenched public-health

policies is like an aircraft carrier making a U-turn. In other words; it

takes a long time.

Some of our most-distinguished NIH scientific

advisors built their reputations on this potentially flawed policy and

may be reluctant to advise the agency to adjust course. Nevertheless, we

need more clarity concerning the true benefits of this drug routinely

used to treat acute SCI.

TOP