Elsewhere, I have discussed various approaches for

controlling urinary tract infections (UTIs) that help preserve the

effectiveness of life-saving antibiotics when they’re really needed.

This article extends this discussion with the intriguing idea that

innocuous bacteria can be used to fight-off UTI-causing pathogens.

As many PN readers know personally, UTIs are

an annoying, recurring health problem for individuals with SCI. It is

estimated that the incidence of UTIs with fever and chills in this group

is ~1.8 episodes annually (Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74(7)).

In the general population, most UTIs are caused by

E. coli bacteria, which, although a normal part of our intestinal

microflora, do not belong in our urinary system. In the case of SCI, a

diversity of other bacteria also causes UTIs.

Antibiotics

Because my doctoral studies investigated how

various antibiotics worked, I’ve especially appreciated their

life-saving importance and how careful we should be to maintain their

power.

Basically, antibiotic development became the

cornerstone in the establishment of the Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA).

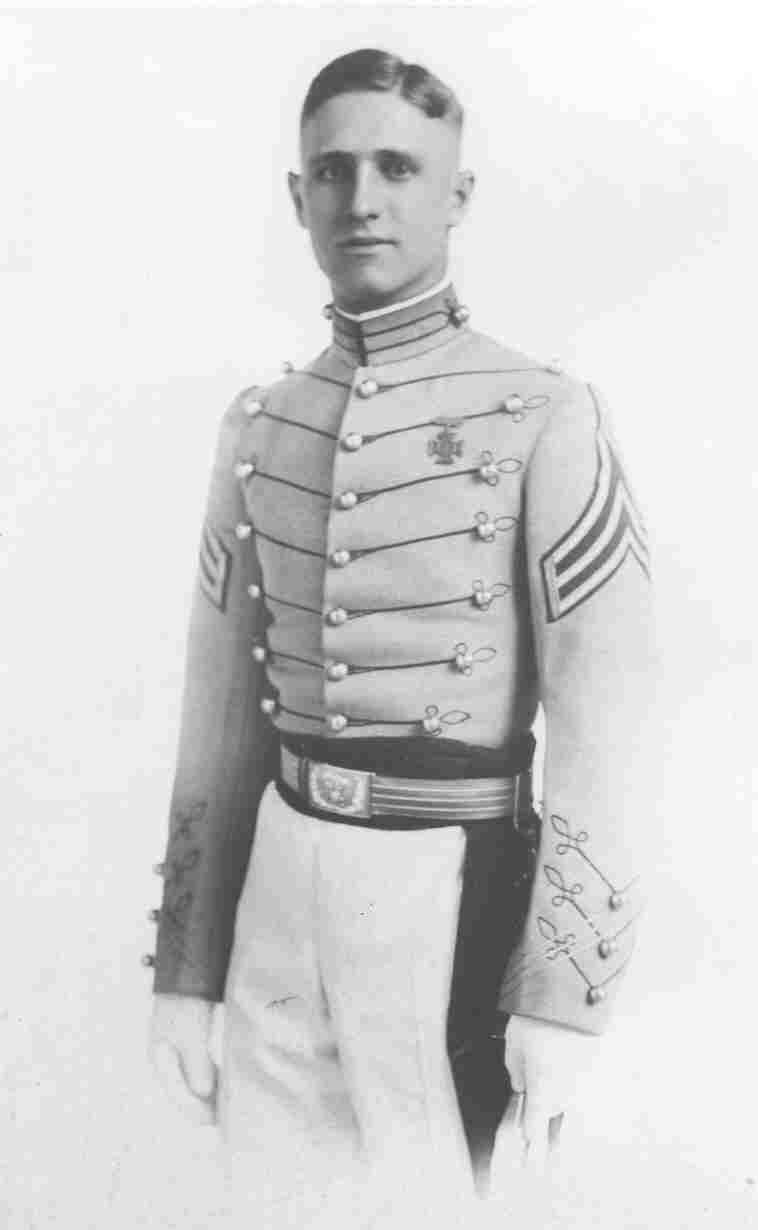

Like the hero in the Oscar-nominated movie Atonement, my g reat-uncle

died due to infection from a wound he sustained charging a German

machine-gun nest in World War I. If antibiotics had been available, he

would have survived, and perhaps I would have met him.

reat-uncle

died due to infection from a wound he sustained charging a German

machine-gun nest in World War I. If antibiotics had been available, he

would have survived, and perhaps I would have met him.

A decade later, future Nobel Laureate Alexander

Fleming observed that bacterial growth was inhibited by a

penicillin-generating mold. As a result of his discovery and the ensuing

large-scale production of penicillin catalyzed by World War II’s

bloodshed, many soldiers wounded later in this war were able to live,

including PVA founders. Since then, scientists have developed numerous

antibiotics, which have greatly increased life expectancy after SCI.

Nevertheless, the growth of resistant bacteria is

of concern for the SCI population that relies on antibiotic use. For

example, research has shown every year two-million hospital patients get

infections that that they did not have when they entered the hospital;

of these, 80,000 die. Figures like these are especially pertinent to

infection- and hospitalization-prone individuals with SCI and underscore

the need to sustain antibiotic efficacy.

In spite of the perception that bacteria are the

“bad guys,” optimal health requires that we maintain a symbiotic,

health-enhancing partnership with them. For example, hundreds of

bacterial species living within our gut are essential for proper

digestion, nutrition, immunological development, and long-term health.

Every time we use an antibiotic, we undercut this bacterial partnership.

By constantly killing off the good guys as collateral damage, we create

a void that may be filled by pathogens or antibiotic-resistant bacteria

that now have no competition for growth. In spite of their clear

importance, antibiotics short-circuit your body’s inherent healing

potential. Tactically, you may be winning many health battles, but you

are weakening your defenses so much you may lose the war.

Because of these concerns, experts recommend that

antibiotics should be judiciously used, reserved for treating

symptomatic UTIs. The chosen antibiotic should be tailored to the

patient’s specific infection as determined by culture, and preferably a

single antibiotic should be administered.

Bacterial Interference

Bacterial interference is a potentially powerful

new approach for preventing UTIs and, by so doing, minimizing antibiotic

use. With this approach, innocuous bacteria are allowed to colonize the

bladder, competitively inhibiting growth by UTI-causing pathogens. Of

course, any antibiotic use during colonization would kill off the

protective bacteria.

Partially

funded by PVA, bacterial-interference studies have been carried out by

Dr. Rabih Darouiche and colleagues at

Baylor-College-of-Medicine-affiliated hospitals, including Michael E.

DeBakey VA-Medical Center and The Institute for Rehabilitation and

Research (TIRR) in Houston, Tex.

Partially

funded by PVA, bacterial-interference studies have been carried out by

Dr. Rabih Darouiche and colleagues at

Baylor-College-of-Medicine-affiliated hospitals, including Michael E.

DeBakey VA-Medical Center and The Institute for Rehabilitation and

Research (TIRR) in Houston, Tex.

As reported in 2000, these investigators studied

bacterial interference in 22 subjects with SCI. All but three were men,

age ranged from 32 to 55 years, and the time lapsing from injury varied

from 5 to 24 months. Subjects were inoculated in the bladder using a

catheter with a benign E. coli strain. Long-term bladder

colonization with this strain (lasting from 2 to 40 months) was achieved

in 13 subjects. Although these subjects had averaged 3.1 symptomatic

UTIs annually before colonization, no infections were observed

afterwards as long as the colonization remained. In contrast, infections

were observed in patients who weren’t successfully colonized and those

who lost colonization.

The next year, the investigators reported the

results of a larger study involving 44 subjects with SCI. Of the 44

inoculated with the innocuous E. coli strain, 30 became colonized

and experienced while colonized a 63-fold reduction in symptomatic-UTI

incidence compared to their pre-study infection rate.

In 2005, the investigators reported the results of

a more rigorously designed randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind

pilot trial. Of the 21 patients whose bladders were inoculated with the

benign E. coli strain, all were men, average age was 52, and 10

and 11 had quadriplegia and paraplegia, respectively. Control subjects

were inoculated with a saline solution. The investigators concluded that

colonized subjects were half as likely as non-colonized patients to

acquire a UTI during the following year.

In a much larger randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled study scheduled for completion in 2008, 160 patients

with SCI or spina bifida are planned to be recruited from five medical

centers in Texas, Georgia, and Illinois. Because only about a third of

colonized subjects are expected to remain colonized for the 12-month

study period, subjects will be randomized in a 3:1 ratio. Subjects will

be treated with antibiotics before inoculation to eliminate preexisting

bacteria, and several days afterwards inoculated with the protective

E. coli strain or placebo.

The investigators also have studied bacterial

interference’s potential to reduce catheter-associated UTIs. Bacteria

that grow on implanted catheters can seed infections on an on-going

basis. The investigators concluded that pre-exposure of the catheter to

benign E. coli significantly reduced catheter colonization by UTI-causing

bacteria.

Conclusion

All life exists in equilibrium with a greater

whole. Whenever we myopically damage one piece of this whole to benefit

another, we create a new equilibrium, which may not be so life-enhancing

over the long term. As an analogy, if we indiscriminately clear-cut our

forests to benefit our immediate needs, we know it’s going to hurt us

down the road as nature attempts to re-equilibrate. Likewise, if we

continuously clear-cut our health-sustaining, bacterial microflora

through repeated antibiotic use, it will inevitably adversely affect us.

By reseeding the bladder with innocuous bacteria after antibiotic

clear-cutting, we create a more health-sustaining environment.

Adapted from article appearing in Paraplegia News (For subscriptions,

go to www.pn-magazine.com).

TOP